Cornell University engineers have created a functional, synthetic immune organ that produces antibodies and can be controlled in the lab, completely separate from a living organism. The engineered organ has implications for everything from rapid production of immune therapies to new frontiers in cancer or infectious disease research.

The first-of-its-kind immune organoid was created in the lab of Ankur Singh, assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, who applies engineering principles to the study and manipulation of the human immune system. The work was published online June 3 in Biomaterials and will appear later in print.

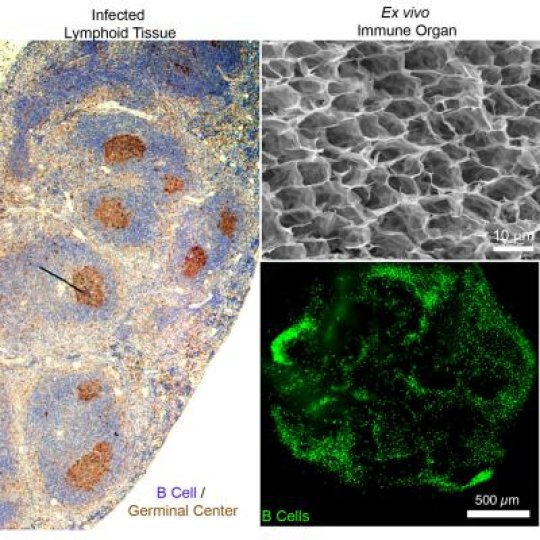

The synthetic organ is bio-inspired by secondary immune organs like the lymph node or spleen. It is made from gelatin-based biomaterials reinforced with nanoparticles and seeded with cells, and it mimics the anatomical microenvironment of lymphoid tissue. Like a real organ, the organoid converts B cells -- which make antibodies that respond to infectious invaders - into germinal centers, which are clusters of B cells that activate, mature and mutate their antibody genes when the body is under attack. Germinal centers are a sign of infection and are not present in healthy immune organs.

The engineers have demonstrated how they can control this immune response in the organ and tune how quickly the B cells proliferate, get activated and change their antibody types. According to their paper, their 3-D organ outperforms existing 2-D cultures and can produce activated B cells up to 100 times faster.

The immune organ, made of a hydrogel, is a soft, nanocomposite biomaterial. The engineers reinforced the material with silicate nanoparticles to keep the structure from melting at the physiologically relevant temperature of 98.6 degrees.

The organ could lead to increased understanding of B cell functions, an area of study that typically relies on animal models to observe how the cells develop and mature.