Chemists at the University of California, Irvine have developed a way to neutralize deadly snake venom more cheaply and effectively than with traditional anti-venom - an innovation that could spare millions of people the loss of life or limbs each year.

In the U.S., human snakebite deaths are rare - about five a year - but the treatment could prove useful for dog owners, mountain bikers and other outdoor enthusiasts brushing up against nature at ankle level. Worldwide, an estimated 4.5 million people are bitten annually, 2.7 million suffer crippling injuries and more than 100,000 die, most of them farmworkers and children in poor, rural parts of India and sub-Saharan Africa with little healthcare.

The existing treatment requires slow intravenous infusion at a hospital and costs up to $100,000. And the antidote only halts the damage inflicted by a small number of species.

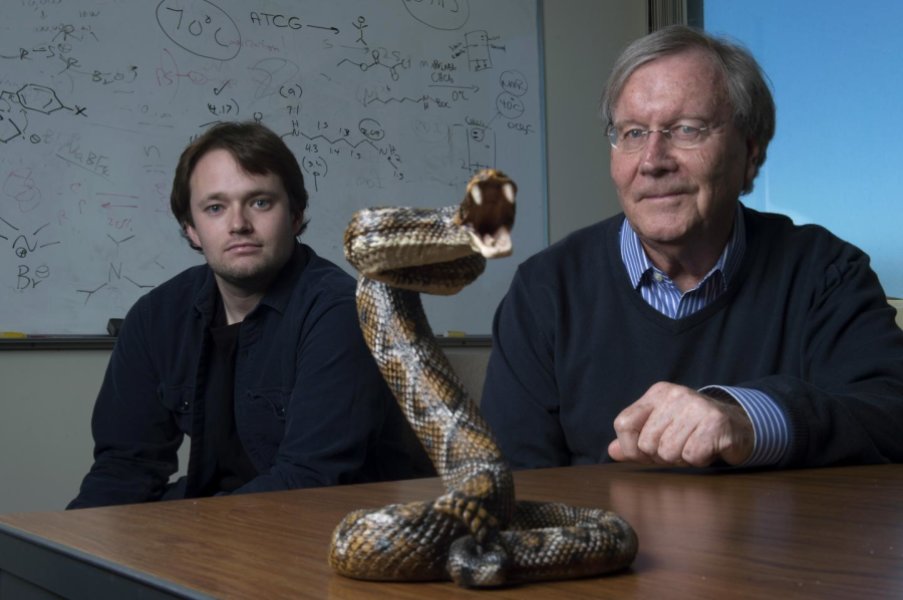

"Current anti-venom is very specific to certain snake types. Ours seems to show broad-spectrum ability to stop cell destruction across species on many continents, and that is quite a big deal," said doctoral student Jeffrey O'Brien, lead author of a recent study published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Zeroing in on protein families common to many serpents, the UCI researchers demonstrated that they could halt the worst effects of cobras and kraits in Asia and Africa, as well as pit vipers in North America. The team synthesized a polymer nanogel material that binds to several key protein toxins, keeping them from bursting cell membranes and causing widespread destruction. O'Brien knew he was onto something when the human serum in his test tubes stayed clear, rather than turning scarlet from venom's typical deadly rupture of red blood cells.