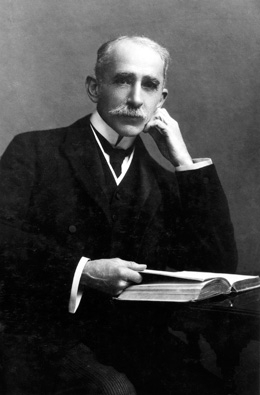

Born at Lancaster in 1849, Fleming was the oldest of seven children. He didn’t take to schooling until he was ten, till which time he was tutored at home by his mother. Once at school, he realized that he wanted to become an engineer. Even at the young age of 11, Fleming set out to work from his own workshop. He built boats and engines and was even successful in making his own camera. His family’s financial situation, however, meant that he couldn’t be trained to become an engineer. What he lacked monetarily, he decided to make up for it through his work. Sir John Ambrose Fleming (November 29, 1849-April 18, 1945), often called a father of modern electronics, is best known for developing the first successful thermionic valve (also called a vacuum tube,a diode, or a Fleming valve) in 1904. His invention was the ancestor of all electronic tubes, a development that gave birth not only to radio communications, but to the entire electronics industry. The modern vacuum tube, the triode amplifier, was then developed by Lee De Forest in 1906. Then the development of radios, televisions, computers, phonographs, Dictaphones, film projectors, and the cultural and intellectual achievements they created are all a direct result of the vacuum tube. The vacuum tube was a key component of radios and most electronic devices until it was replaced by the transistor in the 1970s. Fleming was the "common thread that linked the work" of Thomas Edison, Gugliemo Marconi, and Lee de Forrest, and Nikola Tesla.

Education and career

Fleming showed an early genius for scientific and technical studies. As a student he studied under James Clerk Maxwell at Cambridge, graduating with a first-class-honors degree in chemistry and physics. He was in the top two percent in his class for his B.S. degree. He then earned a doctorate from the University of Cambridge in 1880. Dr. Fleming taught at both Cambridge University and the University of Nottingham. He was the first professor and chair of electrical engineering at the University of Nottingham and University College of London, a post that he held for 41 years. Dr. Fleming was an outstanding teacher in the classroom and very successful as a public lecturer on science. His many awards include the Hughes Medal in 1910, the Gold Alber Medal in 1921, the Faraday Medal in 1928, the Institute of Radio Engineers medal in 1933, and the highest distinction in the Royal Society of Arts. His most important honor, however, was a knighthood, awarded in 1929. In his career, Fleming authored 19 major physics and electronic textbooks and almost 100 scientific articles, many published in leading scientific journals. His 1906 and 1908 textbooks made critically important contributions to electronics. Fleming also authored several creationist books, including The Intersecting Spheres of Religion and Science and Evolution or Creation?

Fleming was the "common thread that linked the work" of Thomas Edison, Gugliemo Marconi, and Lee de Forrest, and Nikola Tesla. He worked with both the inventor of the radio, Nobel laureate Guglielmo Marconi, and the inventor of the electric light bulb, Thomas Alva Edison, in developing a variety of inventions. From Edison, Fleming learned about the ability of a vacuum tube to convert alternating current into direct current. From this information he developed his thermionic tube. When working with Marconi, Fleming helped to design the transmitter that Marconi used in his successful 1901 trans-Atlantic broadcast. In 1904 Fleming designed a vastly improved radio receiver for Marconi. Fleming even helped design and build much of the equipment that makes wireless communications possible. For example, he contributed greatly to the development of electrical generator stations and distribution networks, helping to usher in the electronic age by allowing long distance transmission of telephone signals. He even made significant contributions to radar, which was of vital importance in World War II.

Contribution to modern electronics

Sir John Ambrose Fleming was a leader in the electronics revolution that changed the world. Fleming was instrumental in creating the Fleming valve, also known as the thermionic valve or vacuum tube — a device that is perceived as a marker for the birth of modern wireless electronics. In 1883, following his groundbreaking work on incandescent lamps, Thomas Alva Edison began experimenting with it. On introducing an electrode into the bulb, Edison realized that it could carry a current when it was a positive potential relative to the filament. Fleming, who worked as a consultant for the Edison Electric Light Company and also an advisor for Marconi’s Wireless Telegraphy Company, was well aware of the Edison Effect and had also investigated the same himself. He used this to rectify a weak wireless signal. In October 1904, Fleming had what he describes as “a sudden, very happy thought”. He knew that the oscillations of a wireless signal were too rapid and it was for this reason that the meters indicated zero, which was the mean value. He realized that if the currents were rectified (converting alternating current, which reverses direction, into direct current, which is unidirectional), the signal can be read. Fleming had his assistant test out this idea of his based on Edison Effect and it worked. On November 16, 1904, Fleming applied for a patent for this device which he initially named oscillation valve, but later came to be known as Fleming valve. This diode was an important precursor to the three-element triode, created by American engineer Lee DeForest in 1906. Fleming is often called the father of modern electronics because the vacuum tube that he had invented was the ancestor for all electronic tubes. These tubes laid the basis for radio communications and the electronics industry, before eventually being replaced by transistors in the second half of the 20th century.

As a Creationist

Sir Ambrose Fleming was an active creationist for most of his life. Henry Morris wrote that Fleming was an eminent scientist and one of the most outstanding creationists of the 19th century. Fleming was the first president of the group that had a major influence on American creationists, the British Evolution Protest Movement (EPM). The society was founded in 1932 by Fleming with ornithologist and prolific author Douglas Dewar. The first meeting was held in the office of naturalist and author Captain Bernard Acworth. Other active founders of this group included Professor Douglas Savory, Dr. W. C. Shewell Cooper, and Dr. James Knight, vice president of the Royal Philosophical Society. An active Congregationist, Fleming remained involved in the EPM for most of his life, serving as a president of both the EPM and the Victoria Institute of England, another creationist organization.

A scientist to the core

Fleming argued that, as science progresses, more and more knowledge was uncovered that supported intelligence and design in the universe. A major reason Fleming rejected evolution was because "Organic Evolution is not an ascertained scientific truth fully established by facts but is a philosophy…without regard to the absence of any rigorous proof. In his book Evolution or Creation?, Fleming argued that evolution, like all naturalistic theories of origins, has failed to account for life, the mind, and humankind. He reasoned that, for a theory to be true, it must “not fail in critical places,” as does evolution. After giving several historical examples, Fleming noted that in physics, even one fact can force revision or falsification of a theory. Fleming then lists numerous examples of evolution’s failures, such as the unbridgeable gap between living and non-living matter or between the cell and organic compounds such as methane. His argument in this area, although strong then, is far stronger today. For example, Fleming, in harmony with the understanding of the science of his day, described the cell as a "very small drop or lump of a jelly-like material called protoplasm. Science then knew next to nothing about the cell and its parts compared to today. The mitochondria, rough ER, smooth ER, DNA, histones, and thousands of other organelles and protein systems--plus around 100,000 different proteins in the cell--were all unknown or very poorly understood in 1939. For this reason, Fleming's argument is immensely stronger today. Professors Green and Goldberger wrote just 30 years later: the macromolecule-to-cell transition is a jump of fantastic dimensions, which lies beyond the range of testable hypothesis. In this area all is conjecture. The available facts do not provide a basis for postulation that cells arose on this planet. To postulate that life arose elsewhere in the universe and was then brought to earth in some manner would be begging the question; we should then ask how life arose wherever it may have done so originally. This is not to say some paraphysical forces (meaning beyond material, such as God) were at work. We simply wish to point out the fact that there is no scientific evidence. Since then, the case against molecule-to-human evolution has grown even stronger with the advance of science. Fleming recognized that "evolution is essentially atheistic" and is actually "an attempt to dispense with the very idea of God and substitute for an Intelligent Creator an impersonal non-intelligent agency," namely mutations, time, chance, and natural selection. He concluded from his study of the evidence that the "assumptions underlying Darwin's theory…and the general theory of inorganic evolution have not withstood the valid criticisms leveled at them.