A plant has one genome, a specific sequence of millions of basepairs of nucleotides. Yet how this genome is expressed can vary from cell to cell, and it can change as a plant goes through various life stages, from germination to vegetative growth to flowering to dormancy. Some genes must be turned on and others shut off to ensure each plant cell is doing what it needs to do when it needs to do it.

New research led by University of Pennsylvania biologists and published this week in the journal Nature Genetics has identified small sequences in plant DNA that act as signposts for shutting off gene activity, directing the placement of proteins that silence gene expression. Manipulating these short DNA fragments offers the potential to grow plants with enhanced activation of certain traits, such as fruiting or seed production. The finding may also have implications for understanding gene regulation in both plants and animals.

Plants grow in changeable and susceptible environmental conditions, the part of the genome that is not needed, or that might be providing exactly the wrong information, needs to be shut off reliably in each condition. This information is then passed on to daughter cells.

The study focused on the form of gene regulation known as Polycomb repression. Polycomb protein complexes were first discovered in fruit flies, shown to tightly compact DNA and represent an epigenetic modification leading to gene silencing. Polycomb complexes were later discovered in plants and mammals. In all species, they play important roles in determining cell identity, helping plant cells remember, for example, that they are leaf cells or flower cells.

Despite some studies implicating short segments of DNA called Polycomb response elements, or PREs, in the Polycomb targeting process in flies, questions remained about whether such PREs played a broad role in gene silencing in mammals or plants.

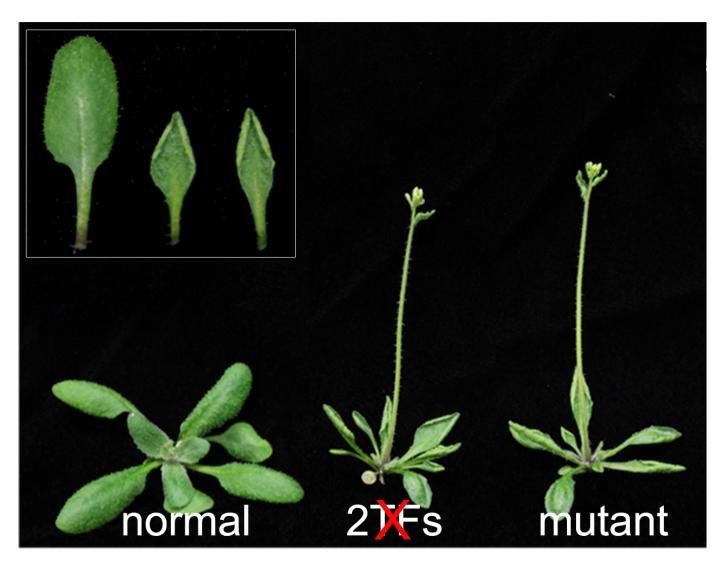

Polycomb complex called PRC2. Using large-scale datasets collected by her lab and others, the researchers identified 170 segments of DNA in the plant species Arabidopsis thaliana that were likely to be PREs. Testing five of these candidate PREs, they confirmed that they acted just as PREs did in fruit flies, recruiting the Polycomb complex to specific parts of the plant genome.

The researchers then identified 55 transcription factors, proteins that bind specific DNA sequences and help regulate how DNA is turned into RNA, that strongly bound to the PREs, and they verified that 30 of them physically interacted with PRC2.

Wanting to know more about what elements in the DNA sequence itself marked it for targeting by Polycomb complexes, the researchers went back to the 170 PRE candidates, computationally identifying short DNA sequences called cis motifs, which are what transcription factors recognize when they scan the genome for their target genes.

With additional analysis, Wagner and colleagues found two of the cis motifs matched up with two of the previously identified transcription factors. Putting these cis motifs in to a plant cell genome revealed they were sufficient for recruiting Polycomb, making them essentially a synthetic PRE.