All the major groups of animals appear in the fossil record for the first time around 540-500 million years ago an event known as the Cambrian Explosion but new research from the University of Oxford in collaboration with the University of Lausanne suggests that for most animals this 'explosion' was in fact a more gradual process.

The Cambrian Explosion produced the largest and most diverse grouping of animals the Earth has ever seen: the euarthropods. Euarthropoda contains the insects, crustaceans, spiders, trilobites, and a huge diversity of other animal forms alive and extinct. They comprise over 80 percent of all animal species on the planet and are key components of all of Earth's ecosystems, making them the most important group since the dawn of animals over 500 million years ago.

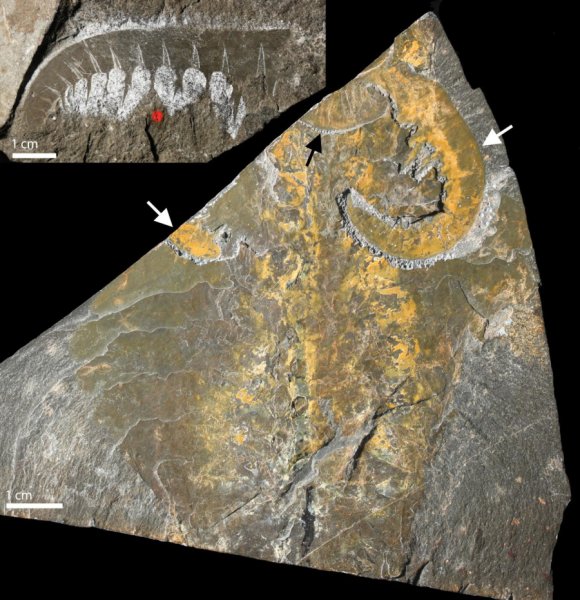

A team based at Oxford University Museum of Natural History and the University of Lausanne carried out the most comprehensive analysis ever made of early fossil euarthropods from every different possible type of fossil preservation. In an article published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencest hey show that, taken together, the total fossil record shows a gradual radiation of euarthropods during the early Cambrian, 540-500 million years ago.

The new analysis presents a challenge to the two major competing hypotheses about early animal evolution. The first of these suggests a slow, gradual evolution of euarthropods starting 650-600 million years ago, which had been consistent with earlier molecular dating estimates of their origin. The other hypothesis claims the nearly instantaneous appearance of euarthropods 540 million years ago because of highly elevated rates of evolution.

The new research suggests a middle-ground between these two hypotheses, with the origin of euarthropods no earlier than 550 million years ago, corresponding with more recent molecular dating estimates, and with the subsequent diversification taking place over the next 40 million years.

Source: University of Oxford