In the plant kingdom, the sexual organ of a male pollen grain grows up to a thousand times its own length as it sniffs its way forth to a female egg cell to deliver its two sperm cells. Now researchers at the University of Copenhagen have advanced the understanding of what makes pollen 'penises', called pollen tubes, grow. The newfound knowledge may prove valuable to understanding human nerve cells.

There's no need for Viagra among 'males' in the plant kingdom. When a male pollen grain, transferred by wind or insects, reaches the female part of a flower, a long, sperm cell-containing tube grows out of it. This tube, known as a pollen tube, can extend several thousand times its own length.

Exactly how this erection works has been unclear for more than 100 years. But now, researchers at the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of Copenhagen have learned what drives pollen tube growth: an electrical circuit, powered by microscopic pumps known as 'proton pumps'. The study has just been published in Nature Communications.

"We were taken aback by how extremely advanced the plant's fertilisation mechanism really is. From textbooks, we understand that pollen tubes grow and push forth by continually building additional floors upon the cell skeleton, like a growing scaffold. However, very little was known about the underlying mechanisms of this enormous growth. Our work has made the world a bit wiser," says Professor Michael Broberg Palmgren from the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences.

Sniffing its way, up to three millimetres a day

Like a sniffer dog, the pollen tube smells its way to an egg cell buried within the female structure, that will eventually become a seed. Tube growth occurs as it continuously extends its tip, a process called 'tip growth'. Pollen tube growth reached roughly three millimeters a day in the thale cress, a weed plant, used in the study.

"The pollen tube is not a rigid tube. It is dynamic and can redirect as it searches for an egg," explains Michael Broberg Palmgren.

Watch video (not from this study) of a pollentube searching for the female pollen. https://youtu.be/

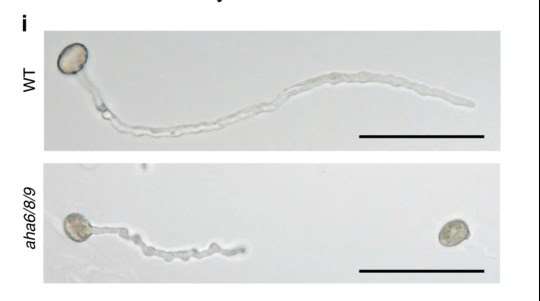

The researchers discovery was made by manipulating a group of genes called AHA in the small plant. These genes are what make it possible for plants to produce the so-called 'proton pumps' that control a pulsed acid-base balance in the pollen tube and generate electrical voltage across its cell membrane. Suspecting that these genes played a role in pollen tube growth, the researchers began 'switching off' some of the genes in various combinations.

"In experiments, we were able to see that the 'mutant pollen tubes', in which we had switched off the genes, were dramatically delayed in their growth and had difficulty finding their way," explains Professor Palmgren.

Result could apply to human nerve growth

Being fundamental research, concrete applications of the result remain unclear. But the new knowledge of how pollen tubes grow by prolonging their tips - 'tip growth' - could be transferable to humans.

"Very little is known about what controls nerve growth - which is hugely important for recovery from nerve or brain damage. Here, our result might prove useful for better understanding the process of 'tip growth', which is how the human nervous system grows as well," says Palmgren.

The professor points out that plant fertilization - and plants in general - are still not entirely understood by researchers.

"The more we investigate, the more advanced plants turn out to be. There are no arguments to suggest that plants are any less than us humans."