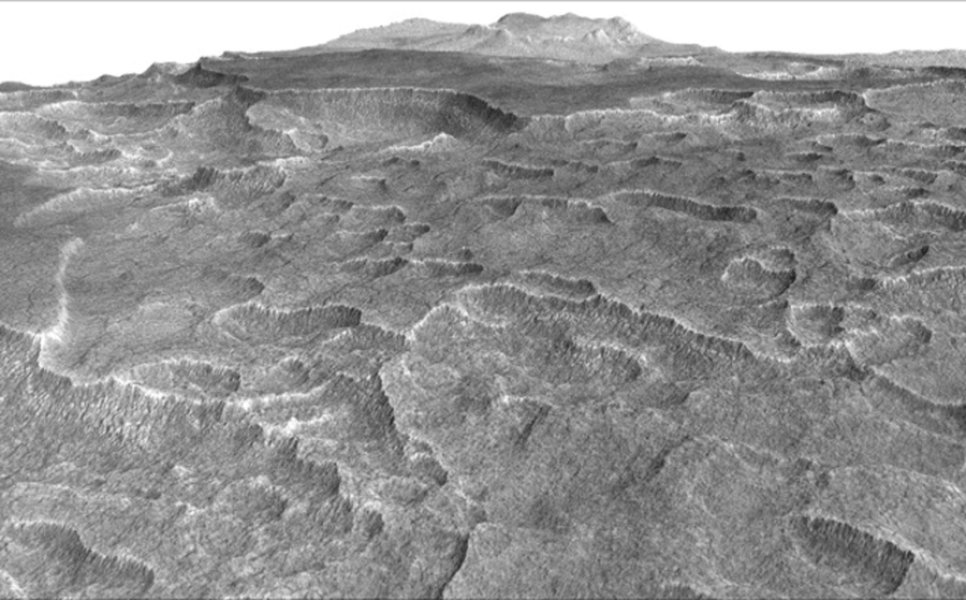

Frozen beneath a region of cracked and pitted plains on Mars lies about as much water as what's in Lake Superior, largest of the Great Lakes, researchers using NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have determined.

Scientists examined part of Mars' Utopia Planitia region, in the mid-northern latitudes, with the orbiter's ground-penetrating Shallow Radar (SHARAD) instrument. Analyses of data from more than 600 overhead passes with the onboard radar instrument reveal a deposit more extensive in area than the state of New Mexico. The deposit ranges in thickness from about 260 feet (80 meters) to about 560 feet (170 meters), with a composition that's 50 to 85 percent water ice, mixed with dust or larger rocky particles.

At the latitude of this deposit -- about halfway from the equator to the pole - water ice cannot persist on the surface of Mars today. It sublimes into water vapor in the planet's thin, dry atmosphere. The Utopia deposit is shielded from the atmosphere by a soil covering estimated to be about 3 to 33 feet (1 to 10 meters) thick.

"This deposit probably formed as snowfall accumulating into an ice sheet mixed with dust during a period in Mars history when the planet's axis was more tilted than it is today," said Cassie Stuurman of the Institute for Geophysics at the University of Texas, Austin. She is the lead author of a report in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Mars today, with an axial tilt of 25 degrees, accumulates large amounts of water ice at the poles. In cycles lasting about 120,000 years, the tilt varies to nearly twice that much, heating the poles and driving ice to middle latitudes. Climate modeling and previous findings of buried, mid-latitude ice indicate that frozen water accumulates away from the poles during high-tilt periods.